How can all students accelerate their mathematical and literacy development?

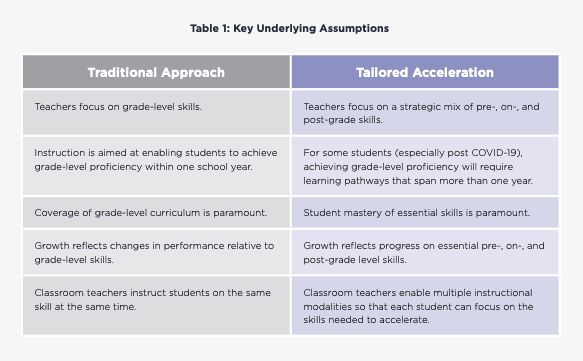

A key component of effective learning acceleration is knowing what content to focus on and when to do so. When students have unfinished learning, it seems only natural that we start by reviewing content they should have previously received. However, this strategy, often referred to as remediation, can actually harm students and exacerbate long-standing inequalities, as one study found.

So, what should we do instead?

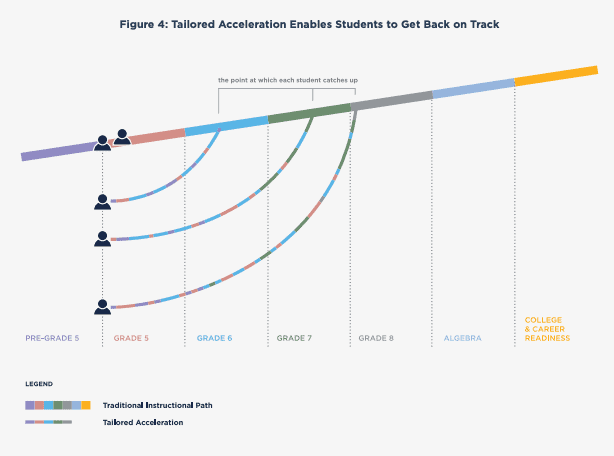

A key tenet of learning acceleration is to allow students to engage with grade-level material while simultaneously addressing any prerequisite skills or concepts they may need. For example, a sixth-grade teacher begins with sixth-grade content and strategically incorporates key fifth-grade concepts when students need them to master current grade-level work. This “just-in-time teaching” ensures that students spend as much time as possible completing on-grade-level work — the key to catching up.

How can educators effectively teach grade-level content while simultaneously addressing learning gaps?

Instructional time is limited, and it can be challenging for teachers to address each student’s unfinished learning while also covering the grade-level material, all in a single school year. Successful learning acceleration requires teachers to understand the content in a different way and know how to prioritize it effectively.

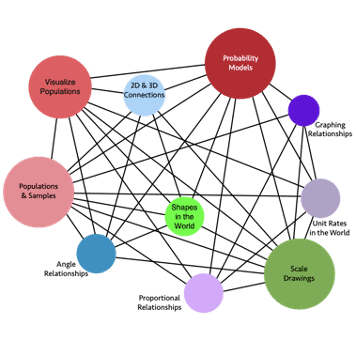

Instead of working lock-step through a grade-level curriculum, this approach asks teachers to regularly assess student learning and then plan instruction that focuses on the discipline’s big ideas, makes connections across standards, and utilizes learning progressions to create logical and efficient learning sequences that weave in necessary practice with missing skills as they go.

What happens when educators make this shift?

When teachers are allowed to make these adjustments, student learning grows more quickly, as demonstrated in the Iceberg Problem and its follow-up report, Solving the Iceberg Problem. This enables students to accelerate their learning and meet grade-level expectations.

Furthermore, when students receive constructive feedback on their current progress, have opportunities to correct mistakes, are shown positive regard, and work toward mastery, their perceptions of themselves as learners improve. This increasing confidence leads to more engagement, persistence, and increased learning. In other words, it creates a persistent positive cycle of learning that helps educators close gaps more quickly. To create this positive cycle, educators need to know what to focus on and when.

Strategic Content Instruction: What’s The Same In Math And Literacy?

Those engaging in effective learning acceleration efforts have distilled a core set of five considerations that, regardless of subject area, those working to strategically plan and teach content should keep in mind. These include:

- Focus on content area big ideas.

- Big ideas are the foundational principles, concepts, and skills of a discipline (see the image for an example of mathematics big ideas). Without them, students never fully grasp how disciplinary concepts are developed and expanded upon. Research shows that focusing on big ideas helps students to see the purpose and relevance in their learning because they better understand how seemingly isolated facts and skills are connected. Educators can use the California content frameworks to identify key ideas that should be at the center of learning. Using these frameworks will help create clarity, coherence, and rigor that is grade-level appropriate.

- Employ learning progressions.

- Learning progressions outline the developmental sequence of skills and knowledge a student typically gains as they progress through a subject area over time. Aligned with state frameworks, they provide a roadmap for teachers to design instruction that builds upon prior knowledge and skills and prepares students for increasingly rigorous content. In essence, they allow the teacher to answer the question, “If my student is here, what is the next thing they need to learn?” Focusing on these concepts and letting go of others can help teachers hone in on the most impactful learning while setting aside other, less critical work. Learning progressions are also essential for learning acceleration work because they support teachers in looking backward through the curriculum to determine the prerequisite skills students may need to understand and succeed with current grade-level skills.

- Build students’ background knowledge.

- Prior knowledge refers to what the learner already knows before the lesson begins. Students are more likely to remember and succeed with new ideas when they are explicitly linked to things they already know, because prior knowledge serves as a framework for learners to better understand new content. Educators can utilize their new understanding of priority content – its big ideas and how concepts develop- to revisit the ideas and skills that directly connect to current learning and help students build meaningful bridges from what they already know to new ones. If students don’t have substantial prior knowledge, use the learning progressions to help them develop the necessary background knowledge to make sense of the current content.

- Strategically teach vocabulary.

- Each subject speaks its own language. To make sense of content, students need to develop fluency in the academic language of their discipline. This becomes increasingly important as students move through the grades. By high school, the number of discipline-specific words students must know is immense. For multilingual learners, a focus on explicit vocabulary instruction is particularly important. While native English speakers continue to develop their language skills, English learners must run twice as fast to catch up to a moving target, especially in content areas. Therefore, as teachers develop lessons aligned with the standards and learning progressions, taking time to explicitly teach, practice with, and require students to utilize the vocabulary will help build their ability to make sense of and grow more quickly in their content area knowledge and skills. To be clear, strategically teaching vocabulary does not mean that educators should always present key terms upfront. Instead, it asks teachers to be mindful of how they introduce and use the language of their discipline and encourage students to practice using it as part of their regular instruction. For more on language development, visit the online courses created by the California Collaborative for Learning Acceleration.

- Utilize high-quality instructional materials.

As the bulleted list above demonstrates, supporting unfinished learning requires deeply knowledgeable educators. When teachers must also create or find all the necessary resources to accelerate learning, the workload becomes unsustainable. Therefore, high-quality instructional materials (HQIM) are key to ensuring equitable access to the grade-level content that all students deserve. HQIMs are defined by their alignment with standards (including the California English Language Development (ELD) standards), have clear learning outcomes, provide rigorous instruction, incorporate evidence-based practices, are content-rich, and are culturally and linguistically responsive. They offer a comprehensive set of materials for educators and include high-quality professional learning opportunities to ensure they can make best use of them. Research shows that using HQIM heightens the alignment of instruction with standards and leads to increased engagement and student learning because it allows teachers to focus on modification, differentiation, and facilitation instead of curating materials.

When utilized effectively, various studies have shown significant increases in achievement across student groups, and HQIM can be a transformational tool for promoting equity. So, ensuring educators have access to HQIM and the support and guidance that enables their use is critical. Schools must, therefore, prioritize ongoing professional learning and coaching opportunities, creating structures for educator collaboration around the implementation of the HQIM in their context to ensure teachers are ready to make the most of the materials.

For more on selecting and utilizing HQIM in California, visit:- California Educators Together, which educators across the state use to access thousands of free, high-quality lesson plans and classroom resources.

- California Curriculum Collaborative

- California-Adopted Instructional Materials

- This report from Ed-Trust West

- The Collaborative for Student Success

- EdReports‘ free reviews of K-12 instructional materials

When systems focus on these five core strategies, they can help create a coherent approach to learning acceleration. These are also valuable foci for common professional learning, allowing educators within and across content areas to develop a shared vision, approach, and tools to ensure students have a cohesive learning experience that accelerates their learning in all content areas.

Attending To Language Development In Strategic Content Instruction

Embedded in the five core areas described above is an overarching focus on language development.

Language development is essential for academic achievement, as students use language to communicate, engage in academic discourse, express their ideas, and make sense of the content shared. The recently released California Literacy Roadmap and California’s English Language Arts/English Language Development Framework identifies language development as one of the key themes of ELA/literacy and ELD instruction. The CA Literacy Roadmap notes:

Language—heard, spoken, signed, read, and written—is the primary means by which humans communicate, and it is the cornerstone of literacy and learning. It is with and through language that children learn, think, and receive and express ideas, information, perspectives, and questions. Attention to language development occurs in all content areas, both formally and informally. Language is enriched when children have daily opportunities to interact with adults and one another and with texts as speakers, listeners, readers, and writers; when all children are comfortable contributing to conversations and feel heard and respected; and when all languages are valued and recognized as assets. Formal instruction includes, but is not limited to, teaching the meaning of words and word parts (e.g., affixes, root words), how phrases and sentences are organized to convey meaning, and oral and written conventions that contribute to meaning (e.g., grammar, punctuation, capitalization). Children learn that language is purposeful and changes according to context, audience, and task.

The Roadmap calls for language development to be intentionally integrated within instruction across all subject areas daily and provides guidance on evidence-based practices for language development for each grade span. Similarly, the 2023 California Mathematics Framework highlights the importance of language development. Chapter 4 of the California Mathematics Framework, titled “Exploring, Discovering, and Reasoning With and About Mathematics,” emphasizes the integration of language development within mathematics instruction, particularly to support multilingual learners. The chapter underscores that mathematical understanding is deeply intertwined with language, and effective instruction must address both concurrently. Thus, while strategies to support multilingual learners are addressed more fully in the Embed Strategic Supports for Diverse Learners section, it is essential to highlight the importance of considering and embedding support for language learners at all levels of planning and development. Therefore, readers will find guidance embedded throughout each of the five core strategies in this section of the Playbook as well.

What’s Different In Math And Literacy?

While all subject areas require a focus on the five areas outlined in the previous section, the application of these concepts in mathematics and literacy is unique. Consider the following modified excerpt from Rethinking Intervention that describes the differences between these two content areas:

Math involves a web of interconnected big ideas. Within any given concept, there is room to connect it to other concepts (which makes math so beautiful!), but some concepts are foundational skills necessary to attain other concepts. In general, we can push forward in math, but we need to understand which concepts are most important to the specific topic we are teaching and reinforce those as we progress. For example, we can reinforce base 10 place value concepts while teaching double-digit subtraction.

Literacy includes distinct components that need to be thought about differently. Foundational skills (how students learn to read) are the most sequential of all the disciplines. For example, students cannot decode multisyllabic words if they cannot first decode a monosyllabic word. There are risks if the sequence of instruction is broken because the skills progressively build upon one another. Comprehension (how students read to learn and express themselves) requires a reader to create a mental picture of what they are reading, build a 3D puzzle out of knowledge of the text’s topic, understand the vocabulary in that text, and develop analysis and communication skills. There are no prerequisites required to dig into the next text or unit — missing the unit on human rights does not prevent a student from engaging in a unit on innovators.

Considering these differences, the sections below provide additional details and guidance for strategically selecting content in math and literacy-specific settings.

Strategically Selecting Mathematical Content

Adopted by the California State Board of Education (SBE) on July 12, 2023, the 2023 Mathematics Framework for California Public Schools guides mathematics instruction in California. The Framework prompts educators to structure the teaching of the state’s rigorous standards around “Big Ideas” that integrate rather than isolate TK–12 math concepts. This approach encourages teachers to think about how the Big Ideas in mathematics connect within and across grade levels in developmental progressions. Check out these free modules the Rural Math Collaborative developed to build knowledge about the 2023 Mathematics Framework and strategies to align your instruction.

Strategically selecting mathematics content requires educators and systems to focus on this set of five core recommendations:

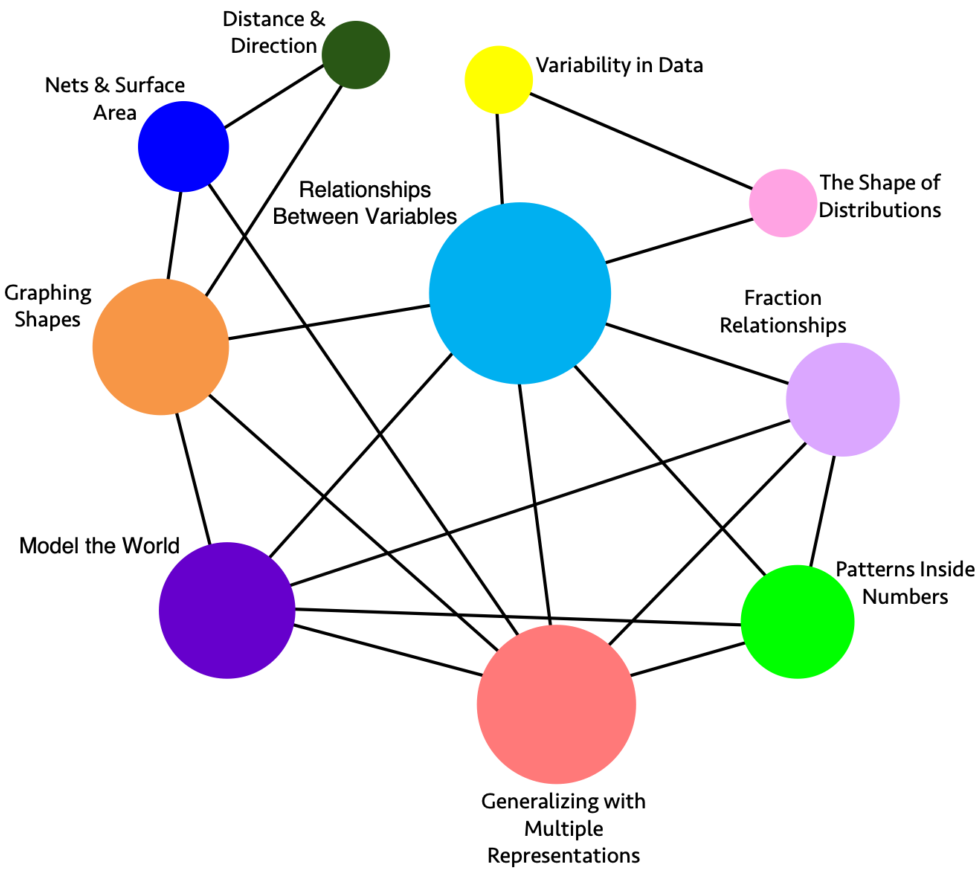

- Focus on mathematical big ideas.

- A “big idea” approach has been shown to engage students and increase achievement because it feels more coherent, connected, and meaningful. The image on the right illustrates how the California Mathematics Framework guides teachers in designing and framing mathematical instruction within their classrooms. It organizes work around the four Content Connections (CCs in green), the eight big ideas or Standards for Mathematical Practice (SMPs in blue), and the three cross-cutting themes or drivers of investigation (DIs in brown). In Chapter 1, the Framework describes the need for authenticity, defined as a task or activity that includes questions and situations about which students actually wonder. Note that authenticity may be real-world or not, such as in games that still inspire curiosity. Being authentic is essential for learners to connect the mathematics to their context, thereby making math more purposeful. The diagram provides a frame for this type of instruction, with the DIs providing the “why”, the SMPs providing the “how”, and the CCs describing “what” content will be learned.

“Big idea teaching” involves intentionally designing instruction around the most important mathematical concepts—big ideas—that often connect multiple standards in a more coherent whole, thereby strengthening mathematical understanding. Focusing on these standards will also address other interrelated and overlapping standards.

- The image to the right shows a Grade 7 constellation map, an example of how the interrelated standards can be addressed by focusing on big ideas. As evidenced by the Iceberg Problem Study, when teachers concentrate on priority content, coupled with regular diagnostic assessments, their students made almost three times the gains as those who adhered only to grade-level content and pacing guides. Therefore, making this shift will yield significant gains for students.

Part of the “big ideas” approach to mathematics in the framework is that concepts are taught as interconnected rather than isolated skills. It emphasizes making sense of problems, reasoning, and applying mathematical knowledge to real-world contexts. Additionally, it encourages inquiry-based learning and student-led exploration to foster deeper understanding and retention of concepts, appreciation for mathematics, and an increased ability to persevere through more challenging mathematical endeavors. Therefore, focusing on big ideas must also involve helping students to make sense of mathematical content by helping them understand how it works and why. Educators can use their knowledge of the big ideas to create multiple ways for students to interact with and represent mathematical concepts, such as using manipulatives (physical and digital), videos, pictures, simulations, and graphic organizers to support students in making sense of concepts and showing what they know about how mathematics works. They can create learning driven by investigations and inquiry rooted in the why, how, and what of mathematics. Students need regular opportunities to explore mathematical concepts independently and with each other, explain their thinking, and develop their stamina as sense-makers. Sense-making focused on big ideas works well for all students, but is particularly important for English learners and students with special needs who will benefit from the connections and practice that comes from this approach.

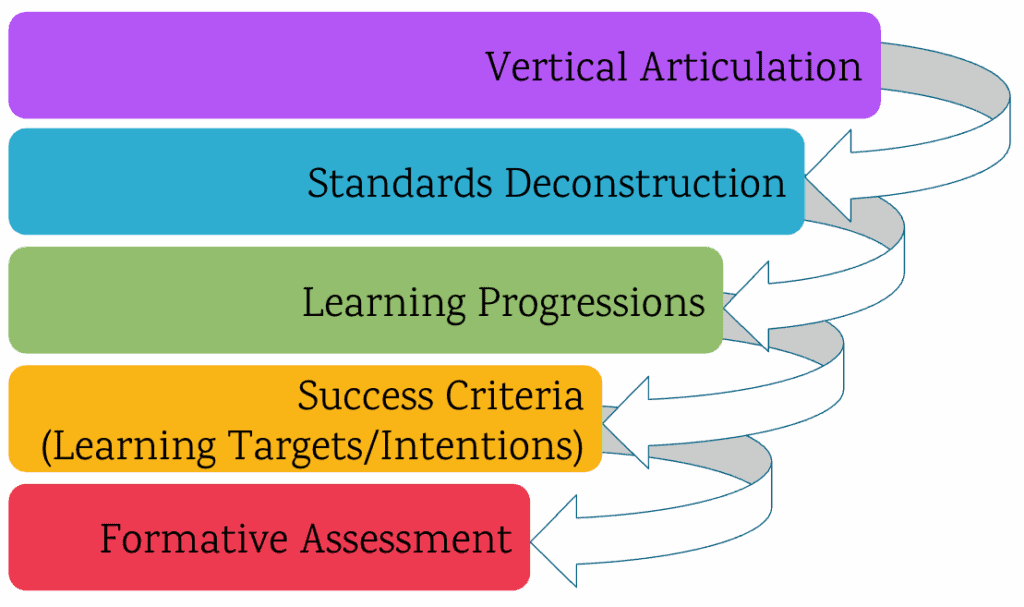

- Employ mathematical learning progressions.

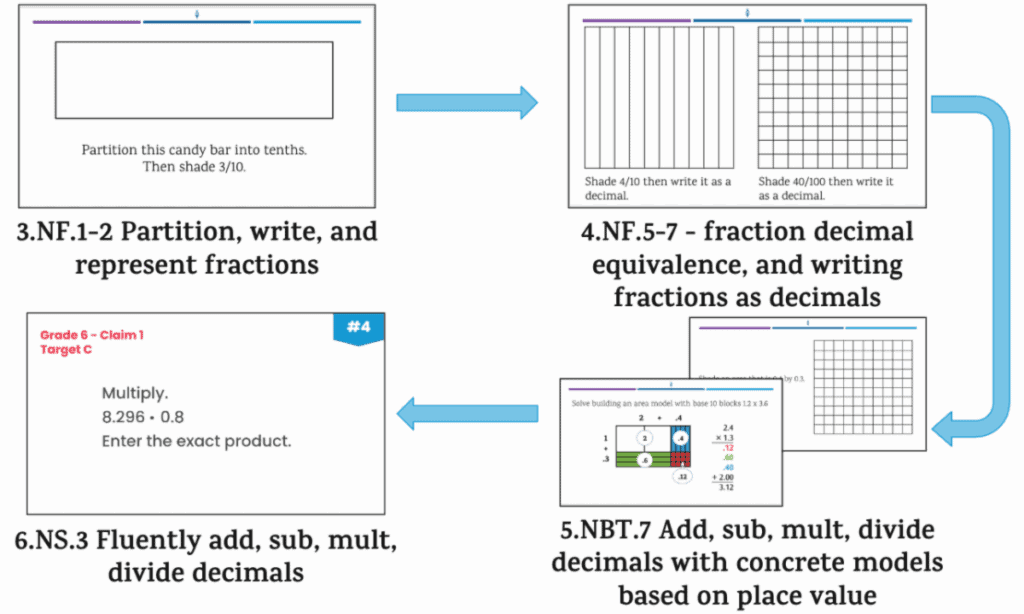

Sequencing instruction to build on students’ prior mathematical knowledge enables teachers to scaffold learning effectively, particularly for those with knowledge gaps. This image, drawn from Building Thinking Classrooms, shows how 6th-grade multiplication of decimals builds on 3rd-grade partitioning and 4th-grade understanding of tenths and hundredths. This is where clear learning progressions become an essential tool for mathematical educators who seek to plan grade-level instruction that weaves in just-in-time supports.

While learning progressions have not yet been developed to accompany the 2023 California Mathematics Framework, other organizations have created tools that can assist mathematics teachers with creating a developmental continuum focused on disciplinary big ideas (see list below). Achieve the Core has also created focus-by-grade -level pages and corresponding priority instructional content pages (math begins on page 42), which can help educators identify priority content.

For more on learning progressions in mathematics, check out these resources:

- The interactive CCSS Mathematics Coherence Map by Achieve the Core illustrates how the standards relate to one another within and across grade levels.

- Expanded Grade-Level Learning Progressions Frameworks for K-12 Mathematics by the Center for Assessment

- CCSS Conferring Continua by The Math Collective

- Future of Education and Skills 2030: Curriculum analysis, A Synthesis of Research on Learning Trajectories/Progressions in Mathematics by Jere Confrey for the OECD Directorate for Education and Skills, Education Policy Committee.

- Learning Trajectories for Teachers: Designing Effective Professional Development for Math Instruction, edited by Paola Sztajn and P. Holt Wilson

- Translating Learning Trajectories Into Useable Tools for Teachers by Cyndi Edgington, P. Holt Wilson, Paola Sztajn, and Jared Webb in Mathematics Teacher Educator.

- Using Learning Trajectories to Enhance Formative Assessment by Caroline B. Ebby and Marjorie Petit in Mathematics Teaching in the Middle School

- Build students’ mathematical background knowledge.

In mathematics, more than almost any other subject, what students already know about a topic strongly indicates their success with new learning. Research shows that assessing students’ prior mathematical knowledge and understanding enables educators to plan, focus, adopt, and adapt new learning strategies, as it helps them construct connections between old and new knowledge. Students’ understanding of mathematical concepts can be enhanced when teachers review prior knowledge and assess understanding before introducing new concepts. When they do so, students gain a deeper understanding of the content, effectively link it to subsequent learning, and increase their ability to apply higher-order cognitive problem-solving skills. Focusing on priority content and utilizing learning progressions can help educators consider the background knowledge students need to succeed with current content and plan how to assess for and build that knowledge as needed.

- Strategically teach mathematics vocabulary.

Learning new vocabulary is essential for comprehending and applying mathematical concepts effectively. Without understanding the plethora of abstract and specialized terms used in a math classroom, both English-only and multilingual learners struggle to comprehend concepts, solve problems, and articulate their thinking both verbally and in writing, as the mathematical standards require. In a mathematics classroom, teaching vocabulary does not necessarily require presenting vocabulary with definitions upfront. Instead, educators can strategically incorporate vocabulary instruction during lessons through authentic, problem-based learning, embedding vocabulary discussion and practice within authentic instruction. The California Collaborative for Learning Acceleration offers self-paced courses on high-leverage, evidence-based strategies to accelerate math achievement, including the incorporation of mathematical language.

- Utilize high-quality instructional materials in math.

The 2023 California Mathematics Framework encourages teachers to adjust their approach to planning and instruction to better align with the best practices for teaching the subject described therein. Coupled with new thinking about planning from learning acceleration, educators have a lot of “new” to deal with right now. HQIMs have been particularly useful in helping achieve these shifts in expectations, especially in subjects like mathematics, which have shown a persistent reluctance to change. For more about what to look for in mathematics HQIMs, look at this resource from EdTrust-West. The California State Board of Education (SBE) formally scheduled a mathematics instructional materials adoption for 2025 to align with the instructional materials evaluation criteria in the 2023 Math Framework. This instructional materials adoption will consider three types of programs: basic grade level for kindergarten through grade eight, Algebra I, and Integrated Mathematics I.

Examples From The Field: What Does This Look Like In Practice?

The example below, adapted from one created by the Fordham Institute, shows what prioritizing key content in mathematics might look like in practice:

Ms. Smith, fifth-grade math: Her first lesson to her class of twenty-two students was on adding unlike fractions. Our diagnostic assessment data showed that twelve of the children were at a third-grade level on that skill—two years behind. The diagnostic showed that some of these students hadn’t yet grasped the need for equal parts when identifying fractions, and others did not yet understand where the values of the numerator and denominator are represented in a visual diagram. Ms. Smith started the lesson by teaching the fifth-grade concept to the whole class. She then had the class work on fully planned, differentiated independent work that was tailored to each student’s mastery of the prerequisite skills—skills meant to be taught in lower grades—that they’d need to understand the new concept. Struggling students had various gaps: some struggled with halves, for example, while others struggled with breaking fractions into smaller units.

Ms. Smith did not go back to teaching third-grade work for multiple days, as it would have left the entire class behind. Instead, for each day’s fifth-grade-level lesson, she focused on filling the gaps that prevented students from grasping it. And then she used RTI hours for those who needed more help. Differentiation in her classroom, however, was relevant to what was being taught that day, allowing students to follow along and soon catch up with their on-grade-level peers. The lesson’s objective applied to all students. She did not focus on filling the years’ worth of gaps at a slow speed by moving backward. She pulled the students up to grade level faster by focusing solely on fractions. The resulting data showed that the whole class mastered, unlike fractions within the specified time.

This example underscores the importance of ensuring that mathematics educators possess a solid understanding of the key concepts in the content and how these concepts evolve across the grades. Her ability to quickly gather data about student readiness enabled her to pivot from the curriculum and offer differentiated supports artfully, ensuring that all students could move forward with the grade-level focus on fractions while simultaneously weaving in prerequisite third-grade skills necessary for success. Utilizing additional instructional time to offer extra support for those with larger learning gaps was also critical for success.

Want to learn more? Check out these resources focused on prioritizing math content.

- 2022 Addressing Unfinished Learning Toolkit (Introduction slides 1 – 8 + slides 9 – 14 for math) Source: Instruction Partners

- CCEE Field Guide resources for Accelerating Learning (ELA, math, science)

- Math fluency inventories by the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics

- California Digital Learning Integration and Standards Guidance Excerpt: Section B— Standards Guidance for Mathematics (pages 101–212)

Strategically Selecting Literacy Content

In July 2014, the State Board of Education adopted the ELA/ELD Framework to support the implementation of the California Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts and Literacy (ELA) and English Language Development (ELD). Developing a single framework that unites these two sets of standards helps California educators support all students as they learn to read, write, and communicate with competence and confidence across all content areas. This means that all California educators, regardless of grade level or subject, are teachers of literacy and English language development. The standards are also notable for positioning cultural diversity, multilingualism, and biliteracy as strengths to be considered in planning and instruction. This means all educators, regardless of content area, must ensure they are knowledgeable and ready to implement high-quality literacy and English language development best practices as part of their instruction, in alignment with the best practices laid out in the ELA/ELD Framework. For more on the ELA/ELD Framework, check out:

- This video provides an overview of the standards.

- CDE offers these resources to support the ELA/ELD Framework.

- The California Collaborative for Learning Acceleration (CCLA) created this set of literacy acceleration modules.

- This webinar recording also provides guidance on California ELA/ELD Standards.

Strategically selecting literacy content requires educators and systems to focus on this set of five core recommendations:

- Focus on literacy big ideas.

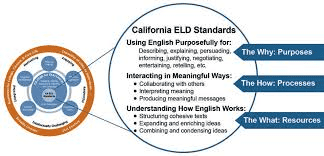

- At the center of the combined ELA/ELD Framework is a set of big ideas called “key themes” that represent the major work of ELA/literacy instruction. As shown in the blue circles in the graphic to the right, these include foundational skills, making meaning, language development, effective expression, and content knowledge. Foundational skills have a sequence of instruction—for example, students need to decode monosyllabic words before tackling multisyllabic ones. The other themes are embedded and taught throughout all grade levels, developing continuously over time.

Part of the “big ideas” approach to literacy laid out in the framework is the idea that literacy is a skill that transcends subject areas and requires students to understand and utilize language for a variety of purposes, through a variety of processes, and using a range of resources (see image to the right). Students must also show increasing competence with these ideas across the literacy domains (reading, writing, speaking, and listening). This approach requires teachers in all content areas to introduce increasingly complex texts with intentional scaffolds, helping students make meaning while developing confidence. This just-in-time support approach to literacy may involve breaking down a comprehension skill, such as identifying themes, into manageable steps, starting with character motivation and plot analysis. For example, a sixth-grade text analysis lesson can build on third and fourth-grade skills such as identifying key details, summarizing, and recognizing character traits. Teachers build upon students’ prior knowledge and guide them through a progression of close reads, using student talk and writing as bridges toward grade-level proficiency and beyond.

- This building and spiraling approach to the big ideas can make it challenging for educators to determine what is “strategically important” in the standards, and so requires educators across content areas to be deeply knowledgeable of the key themes and how to create learning experiences that address the ELA and ELD standards, drawing in content from earlier spirals. It is also important to note that English/Language Arts teachers are not solely responsible for literacy instruction. The standards clarify that literacy instruction is the responsibility of all educators, so educators in history/social studies, technical subjects, and science must also know how to strategically identify and teach literacy content in their classrooms to help students continue to grow their literacy skills in content-embedded ways.

- Utilize literacy learning progressions.

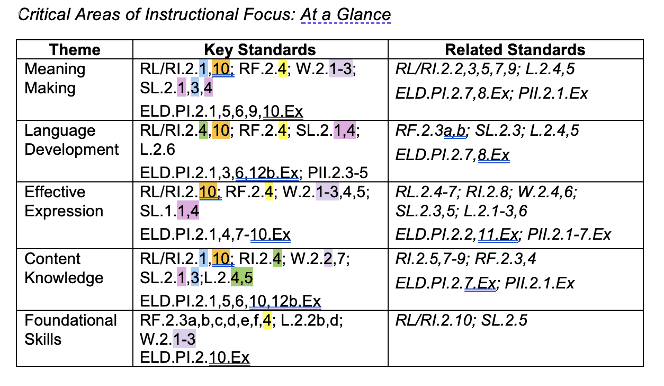

To support the strategic selection of content, the framework identifies a set of key standards for each grade. In May 2025, the California Department of Education released a literacy roadmap and early literacy learning progressions to help educators organize their instruction around both grade-level targets and key themes. By focusing on these standards, educators will also address other interrelated and overlapping standards (see chart from the ELA/ELD Framework included here as an example).

- Priority standards and learning progressions, such as those described here, can also support educators in all subjects to make thoughtful selections about how to weave in just-in-time supports that help students build bridges from where they are with the big ideas to grade-level content. This acceleration approach is critical in literacy, as evidence indicates that having struggling readers read texts below their grade level day after day does not help them “catch up” (Unlocking Acceleration). While students need explicit instruction in foundational reading skills (K-2), once they have developed basic decoding skills, teachers intentionally use their time to focus on instruction that fosters students’ assets and targets their instructional needs, working with grade-level text and providing appropriate scaffolding and knowledge-building to help students be successful.

- Other resources for strategically selecting literacy content include:

- The related standards are outlined in the California Digital Learning Integration and Standards Guidance (Section C, pages 212–486).

- Achieve the Core’s Priority Instructional Content in Language Arts/Literacy.

- A note about foundational reading skills:

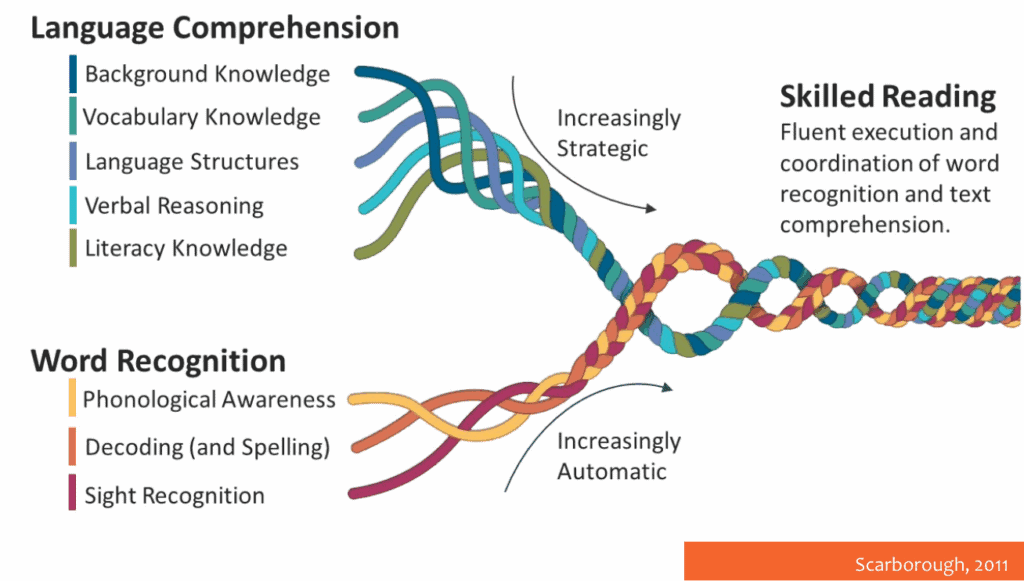

Foundational reading skills are intended to be taught sequentially. Dr. Hollis Scarborough’s concept of the “reading rope,” introduced in 2001 (see image), illustrates how the various “strands” of literacy interconnect and reinforce one another. Therefore, educators are encouraged to use the new California early literacy learning progressions to develop research-based instructional trajectories.

- Given the need for sequential instruction, foundational reading is one area where researchers and experts agree it’s acceptable to revisit and refocus on core concepts if students show a need, as it’s a proven strategy for acceleration. If students missed parts of reading foundations, it is appropriate to go back and teach the skills (including print concepts, phonological awareness, phonics, and fluency) beginning where they left off. Administer a brief diagnostic, such as the Reading Difficulties Risk Screener (RDRS), at the beginning of the year and periodically throughout the school year to determine students’ current levels and plan accordingly. Prioritize each student’s Phonological Awareness, letter identification, letter/sound correspondence, Decoding (and Spelling), and Sight Recognition (the Word Recognition part of Scarborough’s Rope shown above).

- For more information on foundational skills, please refer to these resources:

- CDE: Resource Guide to the Foundational Skills

- WestEd: Developing Foundational Reading Skills in the Early Grades

- CCLA’s free online courses on foundational literacy skills

- Project ARISE offers free online courses on foundational skills

- Build students’ background knowledge to support increased access to literacy.

Building background knowledge is a core component of language comprehension as outlined in Scarborough’s Rope and literacy in all subject areas. The California ELA/ELD Framework and research summarized in the What Works Clearinghouse Practice Guide, “Improving Reading Comprehension in Kindergarten Through 3rd Grade,” also note that explicit instruction, which builds upon students’ prior understanding, such as word recognition, fluency, and vocabulary, supports deeper comprehension and long-term literacy success. In later grades, research emphasizes the importance of building on background knowledge. It notes that students learn more quickly and retain information more deeply when instruction is tied to what they already know and then builds upon it. For multilingual learners who may not have the same background knowledge, it becomes especially important to help students make connections between their current knowledge and new learning. The framers of the Common Core English Language Arts Standards also noted this vital component of literacy instruction, writing a need for deep reading on subjects and reading widely to build the background knowledge necessary to make sense of increasingly complex texts. In other words, knowing a lot about a topic makes reading more complex texts on the same subject easier. Educators in all subject areas can support students in developing and then building on the background knowledge necessary to make sense of content-specific texts.

All content-area educators must consider how to help students become more strategic in their ability to make connections with what they already know as they read and write, thereby becoming increasingly fluent in both general English and the discipline-specific language of the various content areas. Working from the key themes in the ELA/ELD standards and drawing on the learning progressions, educators can intentionally develop learning sequences that build on students’ background knowledge.

- Strategically teach vocabulary across disciplines.

Like building background knowledge, vocabulary knowledge is a core component of language comprehension as outlined in Scarborough’s Rope and literacy in all subject areas. Explicit vocabulary instruction is crucial for learning acceleration because it provides students with a structured and intentional approach to acquiring new words, directly impacting comprehension and overall learning. Focusing on specific word meanings and connections helps students build a stronger foundation for understanding complex texts and engaging more deeply with new information in English and all subject areas.

As students progress through the grades, language instruction moves from learning to read to reading to learn, and vocabulary instruction increasingly turns toward academic vocabulary encompassing Tier Two and Tier Three words (and Tier I words that may require additional focus for multilingual students) which are pivotal in students’ ability to engage with discipline-specific content. Tier Two words, such as “analyze,” “synthesize,” and “evaluate,” are essential for understanding and discussing complex texts across various subjects. Tier Three words, which are specific to particular fields of study, are crucial for grasping subject-specific concepts and terminology. As the Center for Student Achievement Solutions notes, “Effective academic vocabulary development goes beyond mere exposure to words; it involves systematic practice, review, and deep processing. By integrating academic vocabulary into every academic subject and providing cumulative instruction, educators ensure that students internalize and apply these words across multiple contexts.”

Educators must consider which Tier Two and Three words are most critical for students to know and utilize as they seek to make sense of increasingly complex text in their field of study, and how they can support students in using them across domains and themes.

- Utilize high-quality literacy instructional materials.

The California ELA/ELD Framework advocates for a strategic approach to planning and instruction that better aligns with new ways of thinking about teaching the subject. Coupled with new thinking about planning for learning acceleration, educators have a lot of “new” to deal with right now. HQIMs have been particularly useful in helping achieve these shifts in expectations, especially in literacy, which requires complex planning and implementation work to create effective acceleration.

When selecting HQIM, systems will want to ensure that the resources included are equitable and culturally relevant, aligning with the California ELA/ELD Framework requirements. This means ensuring the texts and topics reflect and positively affirm the lives, languages, perspectives, and histories of all students, including historically marginalized populations. You can audit your classroom library to ensure that texts and topics represent diverse perspectives and identities and that the curriculum is culturally relevant. Consider these additional ways to bring more equity to literacy instruction.

For more about what to look for in California-aligned literacy HQIMs, take a look at:

Examples From The Field: What Does This Look Like In Practice?

The example below, modified from one created by the Fordham Institute, shows what strategically selecting content in literacy might look like in practice:

Ms. Jones, fourth-grade English language arts: She introduced her class to a lesson on drawing inferences from a text, and the diagnostic results showed that multiple students were one or two grade levels behind in that skill.

She introduced the fourth-grade standard and then divided the students into groups for independent work or group activities. Her students were required to read a text, note specific details, and then synthesize them to achieve new understanding. The work was differentiated for various ability groups and levels of English language development, but crucially, every child read the same text. The guided groups that Ms. Jones met with were based on the prerequisites required to understand what it meant to infer something. Ms. Jones helped her students slow down and list the important, relevant details on graphic organizers. Then they relied on their background knowledge to make connections, generate predictions, and draw conclusions. Reviewing those “mini-inferences” led to deeper understanding of the text. Finally, that understanding was brought to bear in a whole-group discussion.

Since reading requires a broad range of foundational skills, it would have been easy for her to wander into teaching other skill sets instead of staying focused on one. If a student struggled with sounding out a word, for instance, she did not slip into teaching phonics, but rather stayed focused on the progression skills needed for inferencing. The students connected better throughout the lesson, as Ms. Jones kept them within the range of current grade-level skills.

Educators Need Strategic Professional Learning

As you can see, planning and teaching for learning acceleration that focuses on strategically selected content requires specific knowledge and skills. Teachers need to know their content deeply and know where their students are in relation to it in order to plan the right lessons at the right time. They need to know how to best use their high-quality instructional materials. A 2025 Math Coherence Survey asked California mathematics educators what they are looking for in professional learning, and educators were clear about what they need:

- How to teach with coherence and mathematical practices

- How to connect new curriculum to the 2023 Framework

- Concrete models that show how to implement the California Math Framework in real classrooms

- Support using pacing guides, unit plans, and materials lists

- Support working with diverse learners

- More time for collaboration and planning

Similar needs arise when educators in other subject areas are asked to provide input as well. This is because the type of instruction educators are now tasked with developing and facilitating is not how most teachers learned when they were in school, and it is not how most teacher preparation programs approach learning to teach. So, every educator, regardless of how long they have been teaching, will need support in making this shift. Just as student interventions are targeted for students, so should professional learning be targeted for educators. High-quality professional learning is ongoing and layered. It requires just-in-time, embedded learning opportunities and harnessing existing coaching and mentoring systems to tailor support for educators rather than blanket, one-size-fits-all professional development. The content and resources found in this section can be utilized to plan and develop these strategic and ongoing learning experiences for educators at all levels. If systems truly want to see growth, they need to invest in high-quality professional learning and instructional coaching for educators that builds their knowledge, skill, and efficacy.