INTRODUCTION

Driving Question: What is learning acceleration? Why is it important?

“In the aftermath of this crisis, schools will have an opportunity to provide students, especially marginalized students, with far better academic experiences than they did before. It starts with a commitment to accelerating learning instead of ratcheting it ever downward.”

– David Steiner

We’ve learned a lot over the last two years. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown a clear spotlight on long-standing inequities in access and readiness that exist in our communities that were only exacerbated by the pandemic and the move to online schooling. Early data shows that many California students experienced significant learning lag (the gap between typical learning and learning actual learning) in both English Language Arts and mathematics with students in early grades, low-income students, and English language learners being most affected (see the full report from PACE here). This understanding has created a renewed urgency to ensure that all students, regardless of background or current learning level, have the opportunity to leave PK-12 schools ready for success in college, career, and community life. Getting students back on track and addressing students’ unfinished learning will require a systemic transformation to a student-centered approach that addresses the overlapping learning, behavioral, and emotional needs that support effective learning and teaching. Luckily, there is new research to support our understanding and approaches and many schools in California and elsewhere are already experimenting with new models of teaching and learning that show great promise and from which we can learn. As we close out the 2021-22 school year, we have updated the PAL to incorporate the most recent research and lessons learned from schools and districts to best create and expand the conditions in which our students can thrive.

Defining Terms: Acceleration vs. Remediation

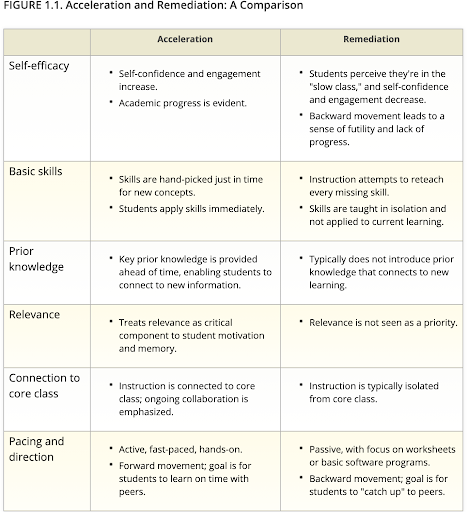

The terms “acceleration” and “remediation” are sometimes used interchangeably but represent two vastly different approaches to learning. To avoid confusion let’s begin by clearly differentiating between them.

Remediation purports to support students who have fallen behind by focusing primarily on helping students master concepts they should have learned in previous years. This often means returning to prior grade-level content and working to fill in holes. When students spend their time in remediation, however, they may not also have a chance to practice with content appropriate for their current grade. This can result in putting students further behind and exacerbating equity and achievement gaps (See the New Classrooms Iceberg Report for more information). Further, we know that repetitive remediation is often composed of “drill and kill” approaches which breed disengaged and reluctant students, frustrated families, and even disengagement from school altogether.

Acceleration, on the other hand, makes it truly possible to get and stay caught up by using what we know about how people learn effectively. Rather than concentrating on a litany of items that students have failed to master, learning acceleration is a system-wide approach that strategically tackles unfinished learning using a whole-child approach. This includes using formative data, a deep understanding of learning progressions, and a relational approach to accelerate learning. Students engaged in acceleration access a laser-focused, high-quality, and rich learning experience by moving students forward and setting them up for success with just-in-time training on required foundational skills. An acceleration approach, in essence, is about building bridges rather than filling holes.

This chart from Learning in Fast Lane by Suzy Pepper Rollins helps clarify the difference between these two approaches.

In a nutshell, remediation is entrenched in the past: what students missed last year and what they need to redo. On the other hand, acceleration focuses on starting students where they are and accelerating them forward using data and a deep understanding of the content to create an individualized and highly targeted pathway for each student.

Accelerating learning is also a matter of equity. As previously mentioned, there are long-standing opportunity gaps that have disproportionately affected students of color, those impacted by poverty, and other vulnerable populations such as ELL students and those receiving special education services. School closures necessitated by COVID-19 only exacerbated these issues. These are the students who are most at risk if they are assigned remediation. Let’s empower them with an accelerated learning approach.

Learning Acceleration: Key Components

We have long known that students learn best when instruction is tailored to their needs. There is a significant body of research showing that acceleration occurs most rapidly when we:

- Employ diagnostic and formative assessments to understand where students are on their learning journey

- Utilize learning progressions focused on key content and big ideas to move students forward rapidly

- Design aligned mastery learning experiences for learners which utilize high-quality curriculum and instructional materials, include rich tasks, and provide students with regular opportunities for feedback and revision. Such approaches breed student agency as they advance student growth and learning

- Personalize instruction at the classroom and school level by employing structures such as Universal Design for Learning, differentiated instruction, and small group instruction aligned to students’ assessed needs to ensure each student is consistently working in their zone of proximal development

- Rethink the school day and learning structures to provide individualized and targeted support such as high-quality high-dosage tutoring that work alongside classroom teaching to ensure all students are getting exactly what they need when they need it

- Intentionally employ research-based strategies that provide access for diverse learners including English learners, students with special needs, and other historically marginalized groups

- Partner with families and community groups to ensure students have the supports, resources, and access they need to succeed.

- Harness thoughtfully selected educational technology to help with assessment, differentiated instruction, and automation of tasks freeing teachers to focus on learning

- Keep improving by using research, data, and experience to constantly learn and adjust our approach

The sections of the playbook that follow will explain each of these key components in-depth, provide resources for further learning, and offer examples from which you can draw.

How we learn matters, too

Learning acceleration is hard work for students and adults alike. People learn best when they feel connected, motivated, and successful. To truly accelerate learning, therefore, we must capitalize on the evidence-based information we have about what helps learners thrive. According to the Learning Policy Institute, key factors that promote learning are:

- Positive relationships and attachments–Both students and adults need to feel capable, included, and connected if they are expected to work hard to catch up. Focusing on building positive learning communities, developing social-emotional competencies, and employing culturally responsive practices will ensure they are ready and willing to do the hard work we ask of them

- Creating connections between what children already know and what they are learning

- Physical activity, joy, and opportunities for self-expression

- Students’ perceptions of their own ability. All people are motivated to learn when they see progress, feel encouraged, and know how to move forward in their learning.

Paying attention to the whole child by intentionally building relationships, social-emotional skills, curating joy and discovery, and addressing trauma in and other needs (more here) is crucial for success. We encourage you to visit CCEE’s Field Guide for Learning, Equity and Well-Being to learn more about these important factors.

It Takes a Village to Accelerate Learning

Building tailored and positive learning opportunities that include the components described above can truly accelerate learning in ways that enable all students to feel competent as they progress rapidly. But teachers cannot do these things alone. Learning acceleration requires systems to carefully rethink the way they use time, staff, and resources to maximize learning gains for students. Consider:

- Prioritizing collaboration. Reorganizing systems to prioritize learning acceleration means finding regular time and space for all stakeholders to work together to reenvision the school day, develop assessments, review data, and align supports for students. Teachers and other members of the instructional team will need dedicated space to learn and collaborate to make this vision a reality.

- Developing professional learning structures. Learning to teach in this way may require a significant adjustment for teachers, teams, and systems. Just as student interventions are targeted for students, so should professional learning be targeted for teachers. Think of just-in-time, embedded learning opportunities and harnessing existing systems of coaching and mentoring to tailor support for teachers rather than blanket, one-size-fits-all PD programming.

- Partnering with families. Research shows a connection between family involvement and academic achievement, particularly in mathematics and English/language arts. Encouraging family engagement is more than a common courtesy; it’s one of the best ways to create a positive learning environment for every student and support student success.

- Broadening our community. To ensure all students have tailored learning, we also need to (re)connect with community-based organizations and others who are invested in helping students learn. Partnering with organizations that can help with tutoring, resources, and experiences is a crucial part of our success plan.

- Adjusting the model. If the pandemic taught us anything, it is that there are many ways to organize learning for students beyond our traditional model of the school day. Learning from those experiences and maintaining those that work best as we return to in-person learning is crucial for success.

Making the Shift: How Will California Schools Accelerate Learning?

As you can see, accelerated learning is not a program to be purchased, but rather a change in approach to supporting students who have experienced learning gaps (which, given the COVID-19 pandemic, is close to all students in California). Learning acceleration should be embedded in all instructional decisions for students: it should be aligned to your vision, linked to your LCAP, and integrated as part of your Tier 1 and 2 MTSS efforts.

The challenge of accelerating progress in California is compounded by the size, diversity, and social conditions of California’s student population. There are more than a thousand school districts in California, serving unique communities with their own needs and challenges, from large urban districts to very small rural schools. California’s challenges reflect not only the state’s size but also its ethnic, cultural, and geographical diversity.

However, California has made some critical decisions to help with the challenge. For example, a barrage of state funding that targeted helping schools and students recover from the side effects of the pandemic, including funding and support for special populations that were uniquely affected. Additionally, California has made significant investments in technology and infrastructure to support students (see more on this here). This not only helped with online and hybrid learning but also will continue to pave the way for accelerated progress. Technology can help assess and target learning to help students meet the standards. Learn more about using technology to accelerate progress here.

What the Playbook for Accelerating Learning (PAL) Offers

We know that doing learning acceleration well is a challenging endeavor. By making these resources available in a concise and actionable format, CCEE hopes to help instructional leaders in California shorten the time it takes to create effective accelerated learning systems and help all students, including our English learners, students with disabilities, and other historically marginalized students, reach the outcomes they deserve. This approach requires an all-hands-on-deck approach and a willingness to adjust from current models. We hope you will find resources in this playbook to get you started, keep you iterating and improving, and provide support at all stages of your work.

In each of the following sections, you will find:

- An overview of current research related to each of the key learning acceleration components laid out above

- Curated tips for critical components of learning acceleration

- Models and examples of learning acceleration in action

- Tools you can use to move your learning acceleration plan forward

- Links to resources for further learning by you and your team

Let’s get started

Use the menu on top of this page to navigate to a specific page of Playbook for Accelerating Learning,

or read one page at time by using the buttons below.