How can schools and educators support the acceleration of English learners and students with disabilities?

California’s classrooms are some of the most diverse in the nation. All students deserve challenging, engaging school experiences that set them on a course for social and economic mobility. Yet achievement gaps among student groups—foster youth, students experiencing homelessness, socioeconomically disadvantaged students, Black and Latino students, English learners, and students with disabilities—have persisted over the past decade. As school systems focus on learning acceleration, it is important to continue centering the experiences and needs of historically underserved students and consider how to build new systems that acknowledge and work with the many assets they bring as a foundation for future learning. While all sections of this PAL speak to the experiences of English learners and students with special needs in the design of learning acceleration efforts, this section will dive deeper into strategies school systems can employ to ensure students who identify in one or more of these ways are honored and strategically supported in their classroom. Though this section of the PAL focuses on English learners and students with disabilities, mindfully incorporating these strategies when building your learning acceleration plan will indeed benefit all students. In sum, focusing on diverse learners is not just about equity; it is a powerful strategy for accelerating learning for every student by creating a more inclusive, engaging, and effective learning environment.

Strategic Supports for English Learners

California is rich in student linguistic resources. As of 2023, approximately 40% of all K-12 students, or 2 of every 5, live in homes where a language beyond English is spoken. Slightly more than half of those K-12 public school multilingual students are fluent in English while nearly 18%, or 1 in 5 are currently classified as English learners (ELs). With the highest concentration and number of ELs in the United States, ensuring positive learning experiences with robust instructional support for multilingual students is critical, not only for their own current educational experience, but also for their future and the ultimate success of California.

Supporting English Learners

Learning acceleration thrives when lessons attend to ELs’ language development needs and concurrently when educators deliver opportunities to grow language proficiency of all students during instruction across content areas. To do so, the state of California has provided clear guidance to educators on how to move ELs forward along the English Language Development Standards (ELD) continuum. Coupled with the state’s ELA/ELD curriculum framework, these two complimentary resources guide educators in designing and providing effective instruction in all subject areas from pre-K to graduation. They advocate that every educator views themselves as a language instructor by becoming deeply fluent in using these tools, in conjunction with their content area curriculum guidance. As promoted by the auspices of Universal Design for Learning, planning instruction that embeds support for language learners from the outset results in access, participation, and language learning excellence for all learners in every classroom.

Some classroom teachers find it daunting to build English language and literacy skills into their content-area instruction, especially when their classrooms contain students with varying levels of English proficiency. Nonetheless, research shows that all students, English-only and English learners alike, benefit when educators intentionally provide explicit instruction and opportunities to practice using academic English in context.

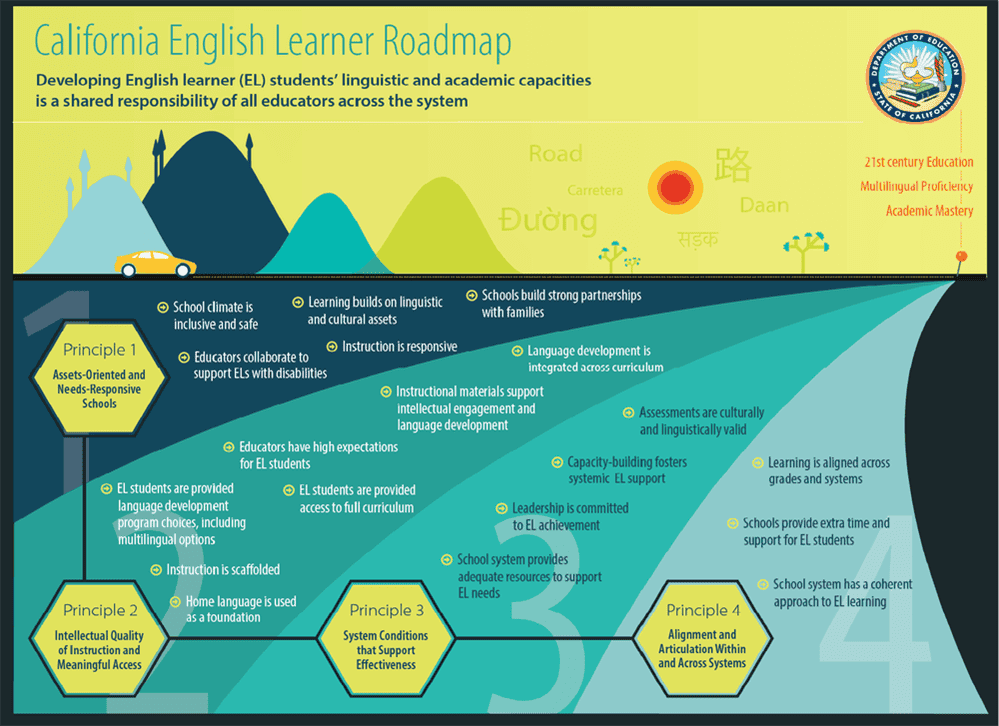

To guide educators, the California Department of Education has curated an in-depth resource called the English Learner Roadmap. The CA EL Roadmap builds on the statutory policy by providing local educational agencies with a dynamic set of guidance materials, including principles, case studies, instructional strategies, toolkits, rubrics, and crosswalks for planning key services, such as during the Local Control Accountability Plan (LCAP) development process. As a keystone influence for schools, the roadmap presents a unified vision: English learners should fully and meaningfully participate in a rich, rigorous education from early childhood through high school, achieve high English proficiency, grade‑level mastery, and have access to multiple-language learning opportunities. The Roadmap serves as a strong resource for educators and systems looking to center the experiences, strengths, and needs of ELs as they rethink systemic school and classroom learning experiences with learning acceleration in mind. Its core principles and approach to supporting ELs are well-aligned with those covered elsewhere in this PAL:

- Principle One: Assets-Oriented and Needs Responsive Schools. Ensuring students and their families are recognized, known, and valued, assuring learning happens in a safe, affirming, and inclusive manner.

- Principle Two: Intellectual Quality of Instruction and Meaningful Access. Offering learning that is intellectually rich and developmentally appropriate, with integrated language and content development and rich participation opportunities.

- Principle Three: System Conditions that Support Effectiveness. Establishing a school system that provides adequate resources and support for ELs and their teachers, supports, assessments, and materials are valid and culturally aligned, and leadership is committed to EL achievement.

- Principle Four: Alignment and Articulation Within and Across Systems. Transforming the school system to provide a coherent approach to EL learning across grades and schools with additional time built in for EL support.

These principles are also outlined in the image below.

For any educator seeking to engage in a self-learning journey to understand and apply the principles, San Diego County Office of Education’s Resource Guide offers an excellent self-paced opportunity to explore each principal. Moreover, the straightforward toolkits developed by Californians Together and shared by numerous COEs across the state, are especially practical and applicable for teachers and administrators desiring hands-on recommendations.

One important fundamental component for accelerating the success of English Learners, established by California’s policy and framework expectations, is the dual requirement to plan and deliver the synergistic instruction of both Designated English Language Development (D-ELD) and Integrated English Language Development (I-ELD). D-ELD, which is a dedicated time for providing ELs academic language learning, should be considered core instruction, a subject matter of its own, and dependent on the ELD Standards with connections to other subject matter standards. I-ELD, on the other hand, is the purposeful design for teaching academic English during each content area for every student, which actually accelerates all students’ learning. Together, both forms for language development ensure all students become fluent in language, literacy and every other subject. Samples of how each can be delivered are exemplified in resources available through SEAL (Sobrato Early Academic Language), a nonprofit dedicated to improving educational outcomes for multilingual learners. Educators may benefit from perusing and establishing professional learning opportunities through their YouTube channel, with practical and inspiring digital video exemplars of instruction, for Kindergarten, second grade, fourth grade, oral language analysis, etc.

In sum, numerous key state resources document and provide guidance for accelerating learning by planning for and confirming that ELs have access to asset-based, high-quality learning experiences grounded in data and occurring in well-developed learning conditions. Under the guidance of knowledgeable and caring educators, their learning can and does accelerate.

Supporting Long-Term English Learners

Recently the state added a new long-term English learner (LTEL) category to the California School Dashboard. The recent enactment requires that LTELs be included in the planning for each district’s annually updated Local Control and Accountability Plan (LCAP). LTELs are now explicitly defined as students who have been English Learners for six or more years without adequate progress in English acquisition.

Typically, it takes 5 to 7 years to develop academic English proficiency. Nonetheless, some notable school districts have managed to reduce the average duration needed to achieve English fluency. Sample successful strategies implemented by districts working to decrease LTEL numbers in their community include:

Still, for many districts, low reclassification rates and slow progress on the ELPAC signal that English learners in their schools may lack appropriate or sufficient support, barring them from accessing the full school curriculum.

Research shows that students designated as LTEL are, for example, disproportionately male, socioeconomically disadvantaged, and/or have special education needs. They are also much more likely to begin school with an English acquisition level of 1 (beginner) and score poorly on the English Language Proficiency Assessment for California (ELPAC) year after year. Recognizing the risk factors early can help early grades educators rethink the kinds of support they offer to students and their families. They can adopt an accelerator’s mindset and check into their beliefs by studying systems that show ELs can and do succeed when learning circumstances are optimal. Educators can become advocates by ensuring asset-based instruction, the data they collect, and instilling a shared belief in capacity building with the students under their care. For ELs who may also have learning disabilities (dually-identified students), determining the nature of the disability separate from language development needs is paramount to tailor instruction to their unique needs. The California Practitioners’ Guide for Educating English Learners with Disabilities provides guidance to teachers and specialists in grades transitional kindergarten (TK)/K–12 to help them appropriately identify and support EL students with disabilities. The guide presents a variety of methods to assist practitioners in providing the highest quality, most culturally and linguistically responsive educational program to all students. Additionally, Project MUSE, led by Imperial County, offers a variety of resources and training to help LEAs advance the achievement of ELs with disabilities. For every typology of multilingual student, offering personalized early interventions and resources that address both language development and other learning needs to ensure continued success and avoid long-term language learning challenges.

For students already designated as LTELs, identifying them promptly, and providing interventions for uplifting literacy, socioemotional well-being and other factors affecting engagement will be key to helping educators better personalize their approach to supporting and accelerating the learning of these students from this point forward. For example, LTELs often have higher rates of chronic absenteeism and lower rates of high school graduation than other ELs, so building in communication structures and collaborations with families and caregivers of LTELs is critical.

Strategic Supports for Students With Disabilities

During the 2024-25 school year, 865,213 students (~ 13% or 1 in 8) of California’s students were eligible to receive special education support and services. The dynamic needs and assets of students with disabilities warrants some additional thinking about how to best support their academic acceleration.

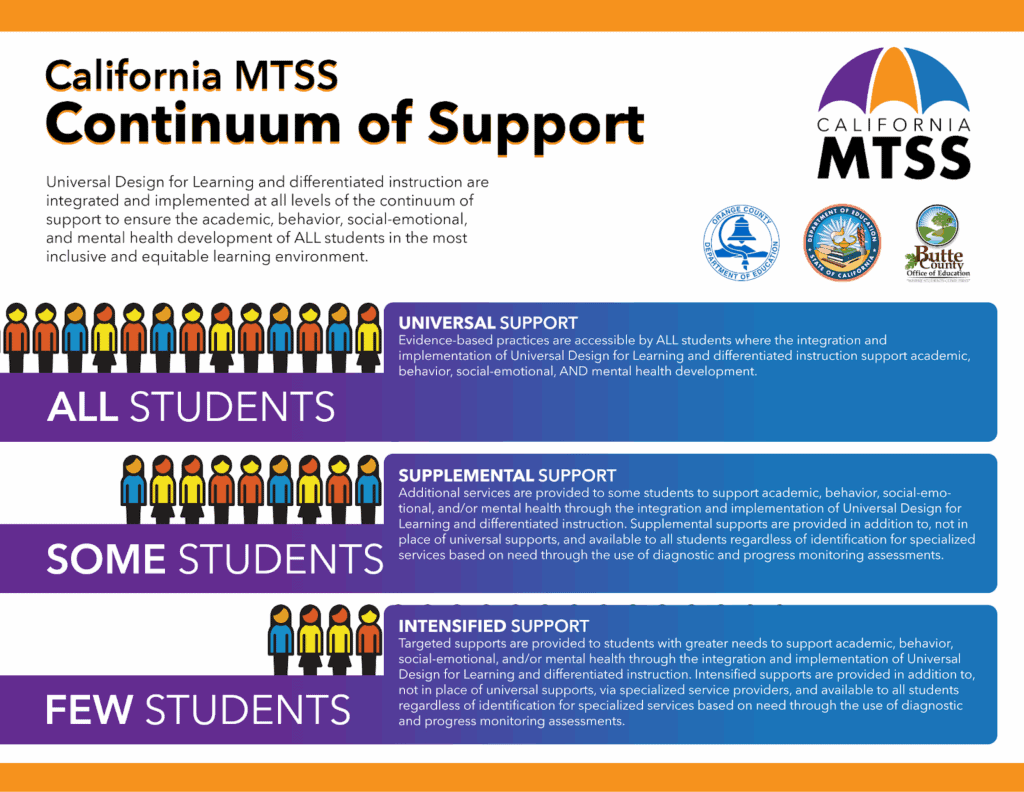

Every student benefits from the type of robust Multi-Tiered System of Support (MTSS) Tier 1 (universal) and Tier 2 (supplemental) aligned learning acceleration supports outlined in this PAL. Starting with a Universal Design for Learning (UDL) approach, offering strategic selection of content, spiraling curriculum, using multiple instructional modalities and strategies, gathering regular data to personalize learning, and planning targeted interventions all benefit students with identified special needs. Embedding these strategies into every classroom will increase the likelihood that each student can find success. In doing so, schools create a valuable opportunity for struggling students to get the support they need, thereby potentially reducing the need for a special education referral.

While raising the levels of personalization may reduce the need for more intensive support, like an evaluation for special education, it does not eliminate it. There will always be a few students who require additional support and accommodations, which is the point of a multi-tiered system of support. From a learning acceleration perspective, all students are first provided with the high-quality instruction and support necessary to be successful in the general education classroom. Utilizing the MTSS model for all students ensures every student can succeed and accelerate their learning with the appropriate level of support.

Rethinking the Role of Special Education in Learning Acceleration

LEAs that are successful with learning acceleration efforts view special education as an opportunity to further leverage the strengths of the student and the system, such as intervention specialists and special educators with specialized knowledge in educational data collection, multi-modal instruction, targeted interventions, and parent/caregiver partnership. The Council for Exceptional Children (CEC) and the Collaboration for Effective Educator Development, Accountability, and Reform (CEEDAR) Center created a set of 22 high-leverage special education practices that all teachers of students with disabilities should master for use across a variety of classroom contexts. These practices can be found in the image below, and you can read more about them here. These practices center on the same core learning acceleration techniques outlined elsewhere in this PAL-collaboration, data-driven planning, high-quality instruction, and intensive intervention as needed. This alignment further solidifies the importance of strategically leveraging special education programming in a school or system’s learning acceleration efforts.

California’s System Improvement Leads (SIL) project elevatesthese high-leverage special education practices along with many otherresources for California LEAs. The SIL project aims to create equitable and cohesive school systems where students with disabilities receive high-quality instruction and support leading to success. How can teams determine whether their LEA has the cohesion and infrastructure necessary to effectively meet the needs of students with disabilities? The Basic Components Tool can be used to assess your special education infrastructure for essential components of an effective system. Ensuring these basic components are in place will ensure your system is primed to successfully implement high-leverage special education practices.

Component 1 of the Basic Components Tool is collaboration and communication, which calls for authentic, active partnerships between special education and general education teams. By working together, they can collectively ensure high-leverage practices are being used in general education classrooms at both the Tier 1 (universal) and Tier 2 (supplemental) levels, that additional scaffolds are thoughtfully built for students who need them, and that all students have the support they need to accelerate their learning in the general education classroom. For example, general and special educators can:

- Support robust Tier 1 best, first instruction for every student through consultation, inclusive learning environment design, positive behavior supports, data collection and progress monitoring, collaborative planning, material modification, and co-teaching.

- Collaborate to create more intensive and targeted Tier 2 supplemental supports for students who are showing a need for additional background knowledge, prerequisite skill development, or social, emotional, or behavioral support. These can occur in class, such as through small group instruction or the development of individualized playlists for students. Or, they may offer strategic pull-out learning experiences such as high-impact tutoring or other RtI2 or PBIS-aligned supports which, as the image illustrates, are considered components of the comprehensive MTSS system.

- If individual students need more intensive support, even with robust Tier 1 and Tier 2 supports, special educators can guide Tier 3 intervention development. This can include intensified support provided by specialized service providers, a referral for an evaluation, and high-quality Individualized Education Program (IEP) development for some students. Special educators can then collaborate with general educators to implement Tier 3 supports, or IEP accommodations and modifications in the classroom alongside continued robust Tier 1 and Tier 2 support. Strong tiered support provided in inclusive settings ensures that students are only removed from the general education setting as a last resort.

The image below provides a visual overview of the MTSS tiers described above.

A Note on Dyslexia

In recent years, dyslexia has garnered increased attention due to advancements in research, growing awareness, and advocacy among educators and parents. As outlined in the California Dyslexia Guidelines, dyslexia is defined by the International Dyslexia Association as a specific learning disability in the area of reading, specifically phonological processing. It is often characterized by unexpected difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition, poor spelling, and decoding abilities, stemming from a deficit in the phonological component of language, even when students have had strong literacy instruction. It can affect all types of students, including English learners. For many students, referrals for special education testing for reading-related concerns occur at the transition from learning to read, to reading to learn (around third or fourth grade), though it may take longer to diagnose English learners because their challenges might be masked by their English language learning process.

To qualify for special education services, a student must be identified as having a disability, and that disability must have an adverse effect on their ability to benefit from their education. For this reason, some students diagnosed with dyslexia may not qualify for special education services. However, when schools implement the kinds of robust, multi-sensory, tiered, personalized learning acceleration-aligned instructional model outlined in this PAL, the diagnosis and services offered by special education may not be necessary. Students with dyslexia particularly benefit from early universal screening and strong structured literacy instruction, especially in grades K-3. These instructional components should be built into the architecture of every MTSS-aligned learning acceleration-focused classroom. California has demonstrated a strong commitment to supporting students with dyslexia with strategic investments in recent years. For example, the state funded the California Dyslexia Initiative to build capacity and resources across California’s educational systems to address the needs of struggling readers and students with dyslexia. Additionally, beginning in the 2025-26 school year, California’s kindergarten, first, and second grade students will be annually screened with newly approved tools for reading difficulties, including dyslexia, providing early identification and support for 1.2 million students.

Educators Need Strategic Supports and Professional Learning

Learning acceleration requires every classroom teacher to see themselves as competent professionals able to work with every child that walks into their classroom. This requires school system articulation and professional development that empowers educators to utilize the high-impact practices described in this PAL and, specifically, in this section. This includes:

- Deepening educators’ instructional and pedagogical knowledge to support diverse learners. Offer ongoing professional learning and coaching to all educators on the knowledge, skills, and strategies needed to support diverse students (including those with disabilities, English learners, dually-identified students, and students with dyslexia) through robust Tier 1 (universal) and Tier 2 (supplemental) instruction. Topics might include: UDL, explicit instruction, asset-based pedagogies, structured literacy instruction, and culturally-sustaining pedagogy. Consider a close look at the California ELD standards, and ensure every educator knows how to guide the simultaneous development of content knowledge and language development, and how to measure the development of language and content mastery. Using resources like Stanford University’s Understanding Language Project and biliteracy resources provided by CDE are a good start.

- Ensuring technologies for learning are accessible to all students. Integrating digital learning for all students requires considering how devices and tools, as well as the internet, should be equitably accessible to all students–including English learners and students with special needs. Educators will benefit from guidance on how to best utilize these tools to increase access to content and learning experiences that meet students where they are on their learning acceleration journeys.

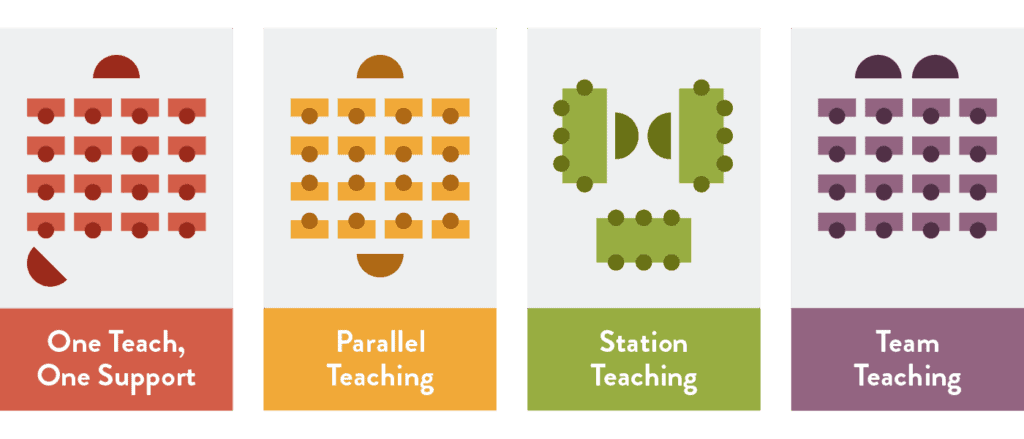

- Teaching professional partnership skills. General educators, special educators, English language development specialists, tutors, paraprofessionals, and other intervention specialists benefit from guidance on how to effectively partner to meet the unique needs of every student. This could include professional learning around co-teaching models (see image), co-planning, and collaborative data analysis strategies.

- Creating regular collaboration time for general and specialized educators. Establish time and structures for teachers supporting the same students to collaborate, share data and ideas, and use data and best practices to plan instruction. Build shared accountability, mutual respect and even fun to strengthen the collaborative relationships among all teaching staff.

- Supporting parent/caregiver connections. Educators will need guidance and support in how to communicate and collaborate with the parents and caregivers of both ELs and students receiving special education services. For example, learning to utilize technologies or services that facilitate communication and resource sharing across languages, or how to provide feedback on students’ progress against ELD standards or IEP goals, would be worthwhile professional learning topics. Make time to establish these strong connections, as communication between classrooms and homes can often be at the bottom of a long list of tasks to accomplish.

- Advocating for multilingual learning even as students develop their academic mastery in English. With the advent of greater technological options for language enrichment, the long history of evidence proving the value of multilingual instruction, and the community-building value of incorporating student/family languages and cultures into classrooms, every school has additional opportunities to acquire new languages. Celebrate students with biliteracy pathway awards or the official California State Seal of Biliteracy. If a comprehensive dual language education program is out of reach, other multilingual pathways before or after school can still bring joyful learning, increase student belongingness, and create the compassionate caring between educators and students that is at the heart of interventions for learning acceleration.