How can data be used to tailor learning experiences in a way that drives learning acceleration for all students?

At the core of accelerated learning is personalized instruction delivered effectively by teachers in the classroom. Various studies over the years show that high-quality instructional content, tailored to the assessed needs and strengths of individual students, leads to increased engagement and the mastery of instructional skills and concepts for all students. Moreover, data-driven instruction promotes a more inclusive and equitable learning environment. By analyzing data on student performance, educators can identify achievement gaps among different student groups, implement targeted interventions, and provide additional resources to support historically marginalized students, thus helping to ensure all students have equal opportunities to succeed and thrive academically.

Before educators can personalize learning, however, they must be clear on the assets each student has built along their learning journey. With this baseline, teachers can accurately pinpoint the specific support a student needs. This is where data-driven instruction comes in.

Data-driven instruction supports learning acceleration by enabling teachers to select specific learning targets and tailor instruction to individual student needs, resulting in more efficient and effective learning. By analyzing data from assessments, educators can identify areas where students would benefit from targeted support, adjust their teaching strategies, and develop precise interventions accordingly, ensuring that every student is more engaged with meaningful tasks and can master concepts before progressing. This evidence-based and targeted approach to instructional decision-making leads to more effective and efficient instruction, ultimately expediting learning and ensuring that students reach milestones and progress at a faster pace.

Rethinking Assessment Use

Assessing student learning is not a new concept in education, but the way educators utilize that data can significantly enhance their ability to support student learning effectively and efficiently. Historically, educators have primarily used assessment as a means to understand what students know at the end of a learning sequence or the end of the year. Data-driven instruction that supports learning acceleration requires educators to do something different– use assessment to support learning, rather than just to measure its results. This approach requires educators to know how to collect, analyze, and use data throughout the students’ learning journey as a means to determine next steps. In essence, educators are being asked to shift from the “assessment of learning” (summative) to the “assessment for learning” (formative) approach, as suggested by Dylan William.

However, whole-class data alone is not enough to support learning acceleration. Student data collection and reviews need to reveal more than a broad understanding of where students generally are; they also need to provide specific information about the individual progress of each student. Insights gleaned from frequent student assessments, paired with literacy and math learning progressions and high-quality instructional materials, enable educators to identify students who may be behind (or falling behind) and offer targeted interventions and customized instructional support to improve student outcomes. For more on learning progressions, see the Strategic Content Instruction section of this PAL. Ongoing assessment is also the opportunity to help educators identify language-related challenges separately for content misunderstandings, which creates more targeted and equitable learning support especially for multilingual learners .This requires real-time, ongoing data from reliable and actionable sources.

To learn more about comprehensive assessment best practices, watch this video featuring Dr. Linda Darling-Hammond alongside California’s teachers and students.

Assessments Useful for Learning Acceleration

1. Language Proficiency Assessments

2. Screeners and Diagnostic Assessments

3. Formative Assessments.

4. Summative and Evaluative Assessments.

This image from Riverside Insights shows the differences between these three types of assessments:

Collectively, these three types of assessment create a balanced assessment system as illustrated in the image below drawn from Chapter 8 of the CA ELA/ELD Framework on assessment.

What to learn more about balanced assessment systems?

- The components of this system are well-described in the Supporting Balanced Assessment within the TK-12 Learning Ecosystem Executive Summary developed by the San Diego County Office of Education.

- Information on creating balanced assessment systems aligned with the California Mathematical Learning Progressions is well-described in this webinar featuring Rincon Valley USD.

- Here are two tools for building assessment systems focused on reading that are aligned with the California ELA/ELD standards and CDE best practices.

- If you’re wondering whether your own assessment system meets the information needs of classroom teachers and school/district leaders, consider completing CCEE’s Assessment System Review Online Learning Path developed in partnership with the National Center for the Improvement of Educational Assessment.

- Finally, here are a few district-specific examples that might provide insight:

While all assessment data are important, for the purposes of learning acceleration in the classroom, assessments for learning — such as screeners, diagnostics, and formative assessments — provide the kinds of data that are most useful for tailoring daily instruction. Let’s explore these types of assessments and their connection to learning acceleration in more detail.

Harnessing the Power of Diagnostics and Screeners for Learning Acceleration

Diagnostic and screener assessments are crucial for supporting learning acceleration by identifying learning gaps and tailoring instruction to meet the individual needs of each student. These assessments pinpoint specific areas where students may be struggling or need more intensive support, allowing educators to implement targeted interventions and provide customized support, ultimately helping students progress at an accelerated pace. Both the California Department of Education and the US Department of Education strongly encourage the use of these tools as a way to inform personalized instruction in the classroom. Let’s start with a quick review of terms.

Universal screeners

Diagnostic assessments

The data from diagnostics and screeners can also inform the development of strategic content instruction (see the Strategic Content Instruction section of the Playbook for more details). Likewise, the data can reveal students who are ready for more advanced instruction. These pretests allow educators to tailor their instruction to meet the specific needs of their students. Instead of reteaching entire units (remediation), educators can accelerate learning by creating strategic instruction that focuses on addressing specific gaps and building on students’ strengths, allowing for more efficient and effective learning. For example, if a diagnostic assessment reveals that a student is struggling with a particular math concept, the teacher can use the standards continuums in the California Mathematics Framework to assess the student’s current level of understanding and plan instruction that will help them progress from where they are to where they need to be. Even if students are missing knowledge or skills from a previous grade, a focus on content connections, big ideas, and cross-cutting themes allows students to continue developing their knowledge while working on grade-appropriate standards. This approach provides targeted interventions and support to help students master the concept while continuing with grade-level content.

Diagnostic assessments can also help students become more aware of their own learning strengths and weaknesses. By understanding their own needs, students are empowered to take a more active role in their learning and work with their teachers to address areas where they need support. This increased self-awareness can lead to greater motivation and engagement in learning. For example, it is crucial to inform students who are English learners about their language proficiency status so that they and their parents can monitor their progress year after year in the subsequent ELPAC status. English learners benefit from recognizing their capacity to eventually become reclassified as English proficient within five years, per state accountability expectations.

By using diagnostic and screening assessments effectively, educators can create a more personalized and efficient learning environment that supports students in reaching their full potential and accelerating their learning from the start. For more on diagnostic assessments, visit CDE’s Guidance on Diagnostic and Formative Assessments.

Harnessing The Power Of Formative Assessment For Learning Acceleration

For the purposes of learning acceleration, the most powerful form of data comes from regular, instructional, goal-aligned formative assessments. According to Black & Wiliam (2001), formative evaluation refers to any activity used as an assessment of learning progress before or during the learning process itself. These low-stakes, standards-aligned glimpses of student progress can include homework assignments, discussions, Q&A sessions, student work samples and portfolios, and other in-class activities.

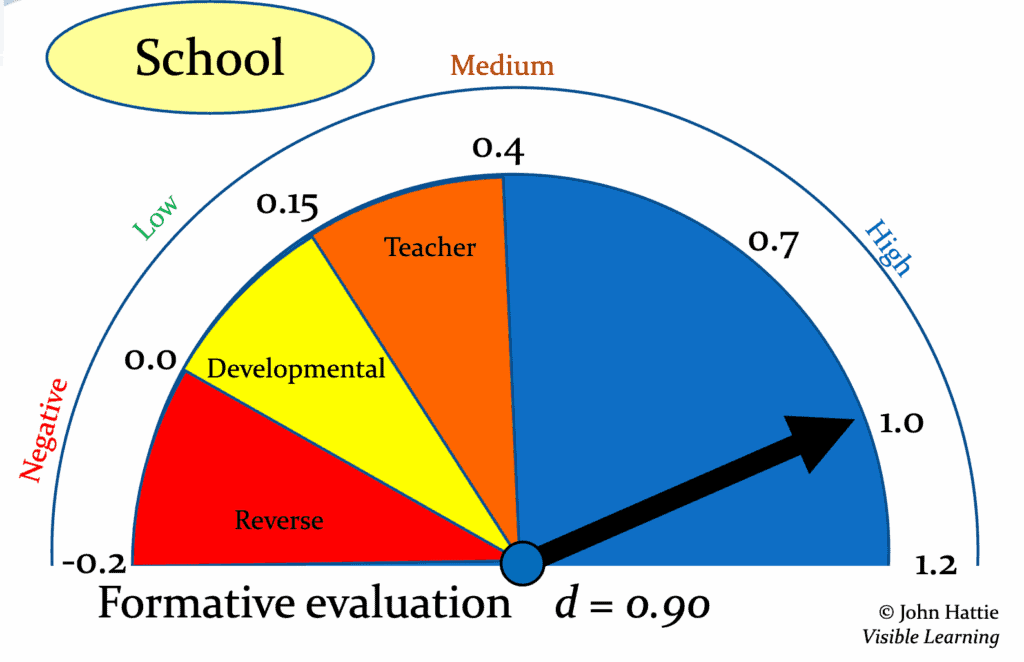

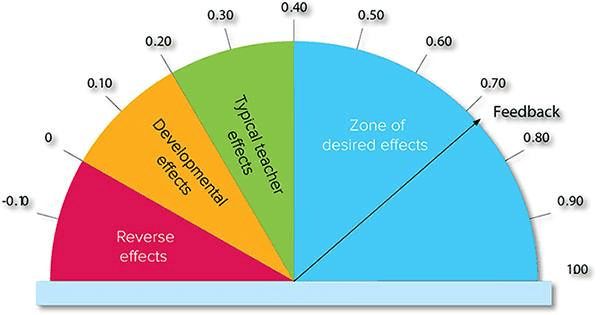

John Hattie, an education metadata researcher and author of Visible Learning, found that formative assessment was one of the most effective tools educators had to influence student learning, with an effect size of 0.90. Effect size suggests that anything over 0.40, which is what we can expect from an average year of schooling, is considered to have a positive impact. Therefore, an effect size of 0.90 suggests that formative assessment has the potential to almost double the amount of student learning expected in a school year.

To truly uncover and address learning needs, educators must understand what students know and can do throughout the school year. This means assessing their knowledge and skills daily or weekly, not just on unit or quarterly benchmarks or standardized assessments. Ensure frequent formative assessments are included in daily lesson plans and drive instructional planning. Entrance and exit tickets, 1-to-1 conferences, written and oral explanations, reading fluency checks, quizzes, classwork, homework, and digital tools (such as polling or assessments embedded in tools like PearDeck or NearPod) all can provide plenty of information for teachers to determine student’s current levels of performance and make data-driven instructional decisions if they are carefully aligned with instructional goals. This iterative process of assessment and adjustment is crucial for maintaining momentum and accelerating learning.

But simply giving formative assessments alone is not the answer. As Black and Wiliam note, “Assessment becomes ‘formative assessment’ when the evidence is actually used to adapt the teaching work to meet learning needs.” Therefore, educators need to know how to utilize the data they collect to make short-cycle, in-the-moment adjustments to instruction and refine their mid-range and longer-term plans based on what they see and hear from students in real-time. They need to hear, for example, about a misconception that arises during partner work and make an immediate course correction, either for that student or for the whole class. To do this well, educators must be very clear about where each learner is going (What is the goal?), where the learner is right now (Where are you in relation to it?), and know how to move the learner forward (What can you do to achieve the goal?). Answering these questions requires educators to be strong at clarifying and sharing learning intentions, analyzing data in relation to those goals, and engineering effective discussion, tasks, interactions, activities, and interventions that elicit evidence of learning aligned with learning progressions. They also need to carefully consider how their own mindsets and biases about learning and students may affect their data analysis, selection of learning tasks, and instruction. The assessment chapters of the mathematics and ELA/ELD curriculum frameworks provide additional content-specific guidance on using assessment to inform instruction and offer strong examples of what this looks like in practice.

Educators keeping the data to themselves is not enough either. According to John Hattie’s research, it’s also crucial for educators to provide specific and clear feedback that helps students understand their current performance in relation to learning expectations and the actions they can take to improve. This descriptive feedback also needs to provide students with the answer to these same questions: What is the goal? Where are you in relation to it? What can you do to close the gap? Tools such as those described in this article can provide a good starting point.

This “just-in-time feedback” is most powerful when it allows students to process their own data in meaningful ways. Processing formative data together provides educators with information about what students know and have learned, and it also offers important insights into how students are learning. It also provides educators a chance to address students’ social-emotional needs as part of the learning process. Learning is hard, and the resilience needed to persist, even when struggling, is an essential part of becoming an effective learner. When students are the owners of their own data and are given the support to develop their learning mindset, they can become full partners in their own learning journey, building stamina, confidence, and a willingness to persist along the way. Utilizing a structured protocol for student data analysis, like this one from the Learning Accelerator, can help facilitate the process.

Then, educators need to create opportunities for students to use that feedback to improve their performance. When the feedback is coupled with teaching students strategies to improve, opportunities for students to immediately apply and practice those new skills, and tools to help them monitor and adjust their own learning feedback from formative assessments can significantly increase students’ confidence, engagement, and learning– another critical element of learning acceleration success. According to Hattie, this type of feedback has a strong effect size (0.75) when used as a stand-alone practice, as illustrated in the graphic.

Want to take it a step further? When students self-assess their own work and utilize the feedback they received from their formative assessments to set their own goals, monitor their own achievement, and reflect on the process of learning, the effect size jumps to 1.33–nearly three times the amount of learning expected in one year, and the instructional move with the highest effect size on Hattie’s list. This is because students recognize the value of the assessment and the data it generates.

Examples From The Field: What Does This Look Like In Practice?

This CDE video series, entitled Formative Assessment in Action, offers six short video vignettes from across the state, showcasing formative assessment approaches in math, science, ELA, and history. The instructional resources utilized in these videos can be found on the Tools for Teachers website.

As another example, through participation in CCEE’s Data Research Learning Network, Rincon Valley Union School District (RVUSD) piloted comprehensive formative assessment practices at Whited Elementary Charter and Madrone Elementary, including foundational training for teachers on formative assessments and effective data practices. Hear more about RVUSD’s learning journey in fostering formative assessment practices by leveraging the mathematical learning progressions from the Ongoing Assessment Project (OGAP) by watching this recorded webinar and reviewing related resources.

For more on formative assessments, explore the following resources:

- CCEE: Insta-Data: Real-Time Formative Assessment that Works

- CDE: Guidance on Diagnostic and Formative Assessments

- CCEE and Center for Assessment: Formative Assessment Micro-Courses

- NWEA E-Book: Making it work: How formative assessment can supercharge your practice

- For formative assessments aligned to big ideas in the disciplines, visit NWEA, MAP, iReady, and Smarter Balance.

- For ELL-focused formative assessment ideas, consider these resources curated by California Together, as well as SEAL.org’s Oral Language Analysis video.

Take A Mastery Learning Approach

A data-driven approach to accelerating learning is a mastery learning approach. To develop a deep understanding of grade-level content and skills, students need to engage in high-quality work tailored to their zone of proximal development (ZPD), full of rich tasks with opportunities for feedback, revision, and time to try again and improve. They require flexible, differentiated, small-group instruction and learning centers that are tailored to the skills they need to practice, as well as brief, targeted, and strategic interventions, such as high-quality one-on-one tutoring, when necessary to build foundational skills and knowledge. This model is built on thoughtfully and regularly collecting and analyzing data from a range of sources, as described in this section of the Playbook (see image below). This approach is meaningful for students because it fosters ownership, confidence, and a sense of control over their learning. Students who say they know how to improve are more likely to persist in the hard work of learning acceleration.

Educators Need Strategic Supports And Professional Learning

Asking educators to develop, administer, analyze, and partner with students to review their own data and set meaningful goals is a time-consuming task that requires both a new way of thinking about instructional planning and significant technical know-how. Rather than expecting that educators will be able to master this new way of work on their own, school systems can help in two ways:

- Providing teachers the professional development they may need to understand what high-quality formative assessment entails for all students including multilingual learners, how to create high-quality assessments that provide meaningful data, how to read and analyze the data in efficient and meaningful ways to analyze assets, adapt plans, and create personalized supports that consider students’ linguistic and other needs, how to take advantage of new assessment technologies, and how to engage with students around the data.

- Investing in formative assessments that utilize technology to provide prompt feedback by measuring student progress in real-time. These assessments can include online quizzes, interactive games, and simulations, and may adjust their difficulty level in response to the student’s performance. Teachers can then focus not on developing or analyzing assessments but on using the real-time data to identify areas where students need additional practice, adjust and personalize their instruction, and support students’ agency by making sense of the data and setting goals for themselves.